Lynne says...

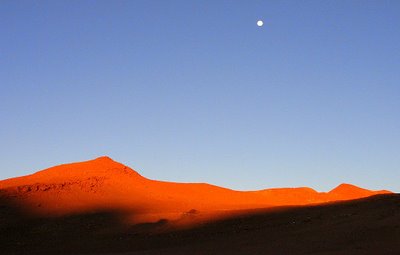

Not only can we now say we have been to the southern most city in the world, we can also say we´ve been to the highest. Potosi sits at a breathtaking 4060 metres above sea level and even a gentle stoll up a hill leaves the most active person out of breath.

The main reason why people venture to Potosi is to visit the working mines. In 1545, silver was discovered in the huge Cerro Rico mountain that dominates the skyline and Potosi quickly became the richest city in Latin America - at times it was bigger than London or Paris. Historically, indigenous and African slaves were forced to work in terrible conditions and many millions died as a result.

Miners buy their Coca leaves at the early morning market

Miners buy their Coca leaves at the early morning marketToday the rich silver seams have all but disappeared but the world demand for lead and zinc mean the mines are still profitable. Potosi remains a working mine but conditions remain atrocious. They have also become a slightly twisted and macabre tourist attraction for travellers on the gringo trail. I was nervous about what lay ahead yet I still found myself signing my life away on a slip of paper.

Just after 8am on our second day in the town we piled onto an old mini-bus that we had to push to start - not a good sign. After changing into full protective clothing including hard hats, headlamps and wellington boots we stopped at the Miners´ Market to buy gifts - it is customary to give a group of men a gift such as coca leaves, dynamite or a soft drink when you visit them at work.

Lynne goes ´native´ and buys a bag of Coca

Lynne goes ´native´ and buys a bag of CocaThe street near many of the mineral processing plants has many small stalls and shops selling everything a miner could possibly need for his work including shovels, hammers, huge chisels, sticks of dynamite, detonaters, fuses and amonium nitrate for a really big bang. Anyone can buy the material to destroy a house, including children, yet Efra, our guide for the day, helpfully explained that Potosi has no problems with terrorism, unlike Europe and the USA. I half expected a bomb to go off in the street at any minute.

The coca leaf is an extremely important part of the miners life. When chewed with an alkali catalyst the resulting juice numbs the senses and helps the miners tolerate altitude and the atrocious working conditions. The bulge in every miners cheek indicates just how important the leaf is to them - each one chews through around 30 grams a day. Ominously, Efra also explained that the miners drink a 96% proof alcohol made from sugar cane to help them forget about the work they do. I tried a mouthful and it nearly evaporated before I swallowed it.

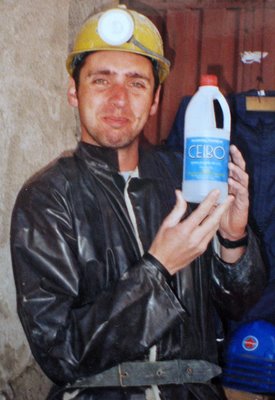

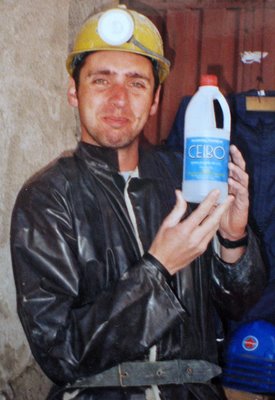

96%? That´ll do nicely

96%? That´ll do nicelyThe miners work in groups of between 10 and 30 often consisiting of family members; fathers, sons and uncles. Each group is completely independent and must buy all the equipment they need - profits are shared out equally and the average monthly wage is $80 US. They also pay the Bolivian government an 18% levy.

Before entering the mine itself we spent around 20 minutes in the processing plant. Here, the minerals are extracted from the rubble through a variety of processes. The machines looked like something out of a Charles Dickens novel and the smell of poisonous chemical filled the air. Miners eagerly crowded around us to receive a handful of coca leaves.

Our next stop was the mine itself. We waited outside the tiny entrance as Efra ran through the safety instructions - basically, touch nothing, including the cables which carry compressed air and electricity. The first few minutes inside were fine. The tunnel was big enough to stand upright and was well ventilated. We stopped at the museum, a small cave filled with various faded pictures and information about the history of the mines. This was far enough for a few people in a group and so we were reduced to four.

The tunnel grew narrower and dustier as we progressed and we were forced to advance by a combination of walking, stooping and crawling. Several times we had to dodge out of the way as carts, heavily laden with rubble, came hurtling out of the darkness, pushed by a couple of miners whose clothes were wringing with sweat. It started to get warmer and stuffier and as the level of oxygen decreased Matt found it hard to breathe and suffered a small panic attack. Our group sat down as we needed to rest after no more than two minutes walking - the lads pushing the carts run for ten minutes at a time.

The minimum legal age limit for a miner is fifteen but nobody checks and boys as young as twelve have worked in the deep tunnels and shafts. Most deaths are caused by the poisonous gases which are released when the dynamite is detonated. Many miners die from respiritory diseases after several years of continuous work although some do go on to work here for up to forty years. Each group chooses how many hours and how many days a week they work. If they don´t work they don´t get paid and as a result they normally work ten hours a day, six days a week.

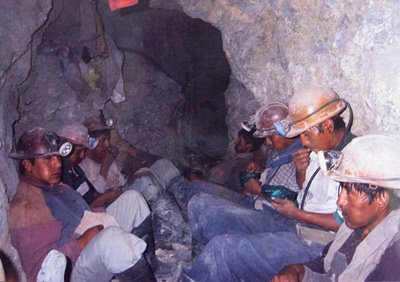

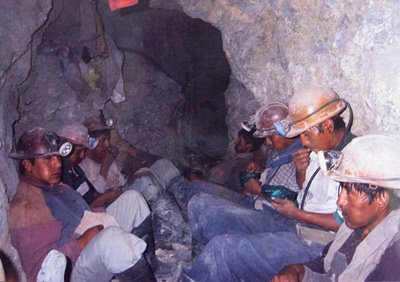

We scrambled down a steep, dusty tunnel to a lower level, choking on the dust. We rested for a while with a small group of miners taking a lunch break. Their dark, dusty faces stared out at us from the darkness. The miners don´t eat any food inside the mine as it causes them to be sick. Instead, they chew silently on their coca leaves.

Miners take their midday break to chew fresh coca

Miners take their midday break to chew fresh cocaEach group has an experienced, older miner. In this particular group it was a forty-four year old man who had been working in the mines for thirty years. His twenty-two year old son sat next to him; his face completely blank and his cheek bulging with coca leaves. We gave them a bottle of fizzy drink and a stick of dynamite as a gift which the elder miner silently took.

We descended two more levels down a rickety ladder with loose rungs. The only way I could cope was by blanking my mind to the thought of how dangerous a situation we would be in if a tunnel collapsed.

Finally we reached the fourth and lowest level. A solitary miner sat with a hammer and chisel, creating a metre long hole for the dynamite. If the rock was particularly hard, it might take him ten hours to create a single hole. The majority of dynamite is detonated at 6pm every day to allow the dust to settle overnight. Arguments and fights sometimes break out if different groups discover the same mineral seam. Instead of using fists, they use their tools and occasionally dynamite to decide who will take ownership.

After two and a half hours underground it was time to leave. Surprisingly, climbing upwards was much easier and faster. Gradually the air grew fresher and we were back in the open air, shocked at what we had just witnessed. Conditions in the mines are primitive and dangerous yet the miners are prepared to risk their lives every day. Efra had promised to give us the details of past accidents after our tour but conveniently he forgot - I was probably better off not knowing.

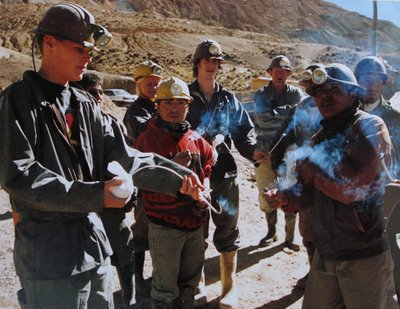

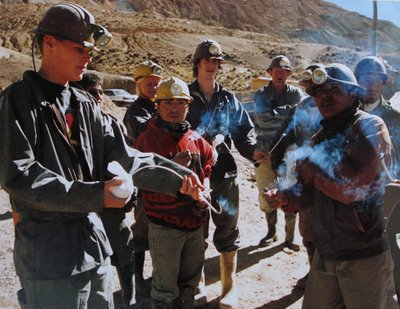

Lighting the fuses to detonate the ´tourist´ dynamite at the conclusion of the tour

Lighting the fuses to detonate the ´tourist´ dynamite at the conclusion of the tour Probably the most bizarre sight on our whole trip. Run man, run!

Probably the most bizarre sight on our whole trip. Run man, run!Matt says...

The tour of the mines was undoubtedly the highlight of our stay in Potosi but it was also a town with bags of atmosphere which made our whole stay incredibly enjoyable. The Koala Den hostel is my idea of how all hostels should be run - friendly staff, a good breakfast, fantastic showers and an excellent DVD collection makes for a happy band of travellers and a good hostel atmosphere.

Such an atmosphere was conducive to myself and an American lad called Dave cleaning up at Texas Hold 'Em one night where we took on all-comers and I won the princely sum of 50 Bolivianos (approximately 3 quid). It must have been beginners luck.

After the flat, fairly uninspiring town centres of Uyuni and Tupiza it was good to be somewhere with hilly, winding pedestrian lanes, a sizeable market area, plenty of bars and restaurants and a general atmosphere of uniqueness. Particularly memorable was my haircut one morning. The barber was lacking a regular electric shaver and delicately gave me my regular grade two crew cut with a pair of what can only be described as hand shears. Potosi, I salute you.